Our Thoughts

A more Holistic path to Emotional Intelligence & Leadership Influence

Like many of you I am indebted primarily to Goleman and Boyatzis for their seminal work in EI, along with the work of Kevin Cashman that started me on this journey. However, given the now generally accepted importance and popularity of the subject, there is also plenty of unsubstantiated information that contradicts not only the best research, but human experience and common sense.

From some of the most popular TED speakers and faculty from leading universities, all internationally recognized, I have recently read or heard that:

- The amygdala is 35 times more powerful than the frontal cortex.

- Most adults are about 9 years old emotionally.

- All decisions are driven primarily by emotion.

These and other similar premises are not only stated as fact, but expanded to tell us how to better manage our emotions, as well as communicate and lead more effectively. Yet each of them is not only ostensibly false and so proven by research, but used to create "solutions" that address neither the reality nor root causes necessary to capture our full potential to become emotionally intelligent, agile and resilient.

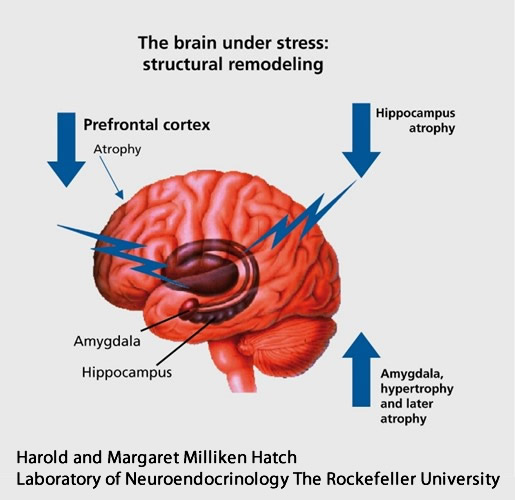

These speculative assumptions about the limbic system can produce a myopic focus that traps us in a reactive cycle of trying to manage our emotions, when there is a more proactive approach that eliminates the need for the constant management and correction of our emotional "elephant" (now popular analogy first used by psychologist Jonathan Haidt). This prevention-based approach enables us to stop trying to "ride the elephant," a challenging and draining task that requires constant corrective action, and instead lead a well-trained and obedient beast down a path of constant emotional growth and effectiveness.

To achieve a higher level of EI and related influence through a more holistic and proactive approach, I suggest a consideration of the following foundational principles in our coaching and leadership development work:

- Don't fall into the typical academic trap of a micro focus on your emotions. Spend time reflecting on your "macro" system, that is, which of your primary internal "voices" (moral, rational, emotional) have most often driven your decisions, communication and behavior with others. Those dimensions in our work are defined as:

- Moral/Higher Voice: The dimension that prompts you to align your decisions and behavior with the two universal values proven to influence most across cultural, national and socio-economic lines: personal integrity and making decisions based on what will benefit the most people affected over the long term. As an abundance of research indicates, this is the dimension that produces trust, engagement, transparent communication, better decisions and learning cultures: in short, teams and organizations that execute with accelerated speed and quality. Our core curriculum equips leaders to recognize their unconscious blind spots and fully develop this dimension to signficantly expand and deepen their influence.

- Rational Voice: The dimension that seeks to reduce uncertainty and variation in order to produce the "safest" possible immediate outcome. With regard to human relationships and implications, it is of course impossible to scan the environment and calculate with any certainty the short-term responses of all those affected by our decisions, and enormously stressful even to try.

- Emotional Voice: The dimension which prompts us to act according to our immediate feelings. Just as with our Rational Voice, a healthy and powerful ally when led by our Higher Voice: something entirely different when we grant it the leadership role of our internal psychological system.

To the degree you exercise and strengthen your higher moral dimension, your rational and emotional dimensions will become increasingly subordinate, integrated and trained to produce creative strategies and positive emotional fuel to support your higher mission. When we act in conflict with our higher moral voice, a host of negative emotions (guilt, shame, anger, resentment, bitterness) are produced in our futile (and usually unconscious) attempts to justify our behavior by blaming others.

If your emotions are the primary driver of your behavior, you may well have an out-of-control amygdala, but you can begin changing that internal dynamic by consciously exercising your higher moral compass as the driver of your future decisions and behavior. To do this consciously requires a slight and temporary reduction in mental efficiency in exchange for a tremendous long-term increase in relationship and leadership effectiveness, a great reduction in stress and a natural state of mindfulness and presence.

- Stop thinking in terms of being "triggered." This implies that someone else can say or do something which then inevitably "fires" an emotional response within you that is effectively beyond your control. Accept responsibility for every emotional response, so you can change your responses, rather than perceiving yourself as a victim and commiserating with others who see themselves likewise.

- Understand how we create our emotions. There is only one possible source, and that is from our past life experience preserved in memories. We create and attach meaning and conclusions about life, ourselves and humans in general from those memories. The meaning we attach generates emotions which reoccur when we unconsciously associate people or situations with those from our past.

- Start small. It is a challenge to get our unconscious thought processes to a conscious level, especially our psychological shadow, but it is a prerequisite to a higher EQ, to say nothing of influencing and leading others more effectively. It is an easier process if we start by reflecting on a few small and immediate decisions that are causing us internal stress and conflict, as that insight will help us be more effective in unraveling the larger and darker web we tend to construct over our lifetime.

Over time this produces a lens or filter through which we now view life and any human interaction: a lens which needs periodic examination and cleaning to remove all the distortions we create to cope with past hurt and trauma, as well as to rationalize past violations of our moral compass. A lot of emotional baggage comes with this distortion, and to unload the weight of these self-imposed delusions produces great leaps forward in EI and relationship effectiveness.

While we have learned a great deal about the limbic system and its interaction with our rational and moral dimensions, as Joshua Greene (Harvard Center for Brain Science) and a recent MIT article (McGovern Institute for Brain Research) point out, we are just scratching the surface of understanding the true drivers of behavior in such an incredibly complex and adaptive system.

What we do know is that our state of emotional intelligence and ability to influence others...or not... is the end result of an internal process that involves our moral and rational dimensions as well. To the degree that process is integrated under the leadership of our moral compass we produce emotional health and intelligence as a natural consequence. To the degree that process is not so aligned, we began to dis-integrate internally and produce the related emotional dis-ease and behavior.

To focus primarily on managing the end of the process is counterproductive and frustrating: in LEAN lingo similar to trying to drive while looking in your rear-view mirror. We would do better to look beyond just "managing our emotions" and do the deeper root cause work of understanding and aligning our internal psychological system to produce healthy emotions and behavior naturally.

Why you should never lie to your Boss

I've come across several articles (Forbes, CBS, LinkedIn) with various iterations on when it is good to lie to your boss, and how to do that effectively: all obviously by highly respected and well-followed experts.

While many external implications and rationalizations are considered in these articles, one critical component is missing…the cost to you of compromising your integrity. When you lie based on your best rationalizations (predictions of how others may respond), or primal emotions like fear, you inevitably weaken the voice and strength of your higher moral compass.

Not only are you now more likely to base future decisions and actions on your strengthened emotional or "rational" internal voices, but you create internal stress as your moral conscience requires continual justification for your past lying. And the assumptions and predictions made from a strictly "rational" perspective, unless you are omniscient, will prove inaccurate and produce unintended consequences at best.

This weakening of character and increase in stress is so incremental that it is often not discerned until years later, after the incremental cost has turned into a wealth of lost opportunity, productivity and relationships. The best way to avoid that sad state is to prevent it by an unyielding devotion to integrity and the courage not to compromise it.

There are simple ways to avoid lying in any of the scenarios outlined in these articles, effectively address the immediate dilemmas, all the while preserving and strengthening your integrity. If you ever find yourself in one of these scenarios, please consider the long-term implications to your integrity, the implications for your psychological health, and your future ability to engender the trust and respect of others before taking the easy way out.

Roy HolleyBACK to the FUTURE for more effective LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT

Like many of you I have read countless articles in CLO et al. publications reminding us how far the L&D function is behind the market and effectiveness curve, a well-documented fact especially in leadership development (in a Korn Ferry Institute Survey 55% of senior leaders ranked the ROI from their leadership development programs in the "fair to very poor" range).

The vast majority of these articles encourage more innovation, especially in the use of technology and blended learning. The most recent article I read even mentioned how "today's brains have changed," citing the numerous platforms and apps we use to communicate and consume information. There is, however, no research to support any fundamental "brain change" theory and an abundance of research indicating that our brains, effective adult learning mechanisms and human nature remain essentially unchanged, in spite of advances in technology and communication mediums.

Obviously knowledge and information can be effectively shared through the use of digital and on-demand applications, when new knowledge is the primary objective. However, in leadership development, new knowledge does not correlate to meaningful and sustained changes in values and behavior for obvious reasons. If, in fact, we are interested in achieving a meaningful and lasting ROI from our leadership development initiatives, it would be worthwhile to consider what has not changed in our VUCA world, and how we can build on that solid foundation to be more effective, rather than chase innovation and efficiency at the expense of return.

Human nature: The exhaustive research of Shalom Schwartz et al. indicate that the values to which humans aspire, and are influenced by, remain both few and consistent across all cultural and demographic lines. To help leaders understand and reduce the unconscious gaps between their behavior and these universal values, thus increasing their influence, is a challenge requiring deeper expertise from practitioners as well as intensive and sustained human interaction.

Practice makes perfect: As Peter Senge reminded us over two decades past, we fail to apply this axiom in organizational life at our own peril. Which of us would dare hire an attorney or surgeon that had learned their "practice" by looking at endless slide decks or digital content? Or believe it a good investment of time and money to see a professional sports team or orchestra that spent 90% of its time playing vs. learning and improving through practice? Is it any wonder our ROI for leadership development is so paltry when, in pursuit of efficiency and scaling, we ask our leaders to risk, fail and learn while "in the game?"

Adult Learning: Our success in helping leaders translate new and deep insights into lasting behavioral change has been, for two decades, based on the integration of experiential scenarios, new knowledge, reflection, practice and application (Kolb). Recent research has reminded us that when new information or knowledge is communicated through the traditional expert-to-learner model, irrespective of whether the channel is high-tech or high-touch, 70% of the content is lost within 24 hours.

Research by Oxford Strategic Consulting found that those under the age of 35 are the least likely to embrace digital when learning leadership: only 11% preferred digital over face-to-face learning. It should be no surprise given how much they recognize and value human connectivity, along with meaningful growth and development, vs. checking off another L&D course…yet based on most of the opinion pieces I have read who would have suspected?

We certainly need to enhance our approaches to leadership development, but in chasing innovation and scale, perhaps we ought to consider why our return and effectiveness seems headed in the wrong direction and ask some different and deeper questions?

Roy HolleyDid You Hear What You Just Said?

Being present and truly listening to others are obvious prerequisites for effective leaders. But how many of us are skilled at listening to our own words, and understanding their implications for our own future growth or decline as leaders?

Recently I have noted several political and business leaders using expressions such as, "I had no choice but to….," or "Our company was forced to….. etc." I began to research the use of such language in our culture and found a frightening amount of similar examples.

One of the more egregious cases occurred on a D.C. Metro train in July of last year. A young man murdered a fellow traveler, stabbing him dozens of times, returned to stomp on his body, and then proceeded to rob others on the train. Those who interviewed witnesses after the fact revealed how many on that train said that they "had no choice" but to watch in silence while their fellow passenger was stabbed until dead over a period of several minutes. They even encouraged and colluded with each other to ensure no one intervened to stop a 125 lb. man who was vastly outnumbered. As one passenger stated: "I wanted him to think he could walk away from this, and that's what he did." She "had no choice" but to watch the murder because her father was also a passenger.

How could so many speak the language of victims with no options, when the truth is so obvious? Using such delusional language does not remove our unconscious awareness of self-evident truth, or our earned and enduring guilt, it just strengthens the walls of the prison we have built around ourselves. It is a prison constructed from the delusion that we are not responsible, which then limits our ability to respond. Over the years the "operating space" in our cell (our ability to choose and respond) grows ever smaller. The resulting carnage in life and organizations may not be as immediate or evident as a man bleeding to death in front of us, but in the long run the damage is just as deadly to our own physical, emotional and mental health as it is to those around us.

It is easy for us to think we are enlightened and immune to such thought and language. However, I still clearly recall standing with Bob Spiewak (my capable mentor) on the beaches of Cape Cod during one of our leadership retreats, speaking with an executive leading a merger between two major companies. This leader became visibly emotional as he discussed why he "could not tell the truth" to his employees about their future plans for workforce reduction, plans which of course, leadership had "no choice" but to execute in order to capture the potential financial synergies.

What is most striking to me these years later is not what he said, but the fact that he had truly convinced himself that he had no choice but to lie to his employees in this scenario. He was certainly a prisoner, but one of his own making, and he must have known that at an unconscious level given his obvious distress. Had he just had the presence and courage to listen to his own voice, he could have liberated himself from the victim status he had falsely constructed.

As important as it is for leaders to listen to others, it is for most of us more challenging to listen to ourselves, and then objectively evaluate our beliefs and values based on our own words. As painful as it may be initially (speaking from personal experience), it opens up a world of endless possibility and growth for ourselves and others.

Someone shuffling around within the shrinking confines of their self-constructed prison cell is hard to follow…and why would one bother to try? A person who assumes full responsibility, and thus has the ability to respond in any situation…that is the person I want to follow. A good starting point for determining where we fall on that spectrum begins with listening to the sound of our own voice.

Roy HolleyOne "Small" Decision, One Giant Leap in Leadership

The anniversary of that first small step onto the lunar surface is approaching, and given the complexity and uncertainty challenging leaders in the current global environment I thought it worthwhile to revisit how Neil Armstrong was chosen for the leadership role in such a complex and historical accomplishment (at the time the mission was thought to have about 50% chance for success and Nixon even had a speech prepared in the event of failure and loss of life). First, of course, he had the expected resume: record EVA time (working outside in space), Doctorate of Science in Astronautics from MIT, had improvised an effective method for rendezvousing in space after an initial failed attempt on Gemini 9A, etc. And he had passion for the lead role. As the head of Mission Control at that time wrote in his memoir Armstrong "desperately wanted that honor and wasn't quiet in letting it be known."

Oh wait a moment….those are not the credentials or words of Neil Armstrong, but rather of the second man to walk on the moon, Buzz Aldrin. The credentials for Armstrong? Average grades at Purdue, accepted at MIT but declined to attend, Master's degree from USC, less EVA time, and this strong precedent against him. In ten prior Gemini flights the pilot (Aldrin for Apollo 11) always led the space walk. And Armstrong did no lobbying or self-promotion in search of the leadership role.

So how in the world did a humble man so disadvantaged by precedent and credentials get chosen for the leadership position that will live forever as such a powerful inspiration? In reviewing his life it becomes obvious how "small" decisions led to this giant leap in his career. But how is that relevant to leadership and decision-making over forty years later?

Forty years later we hear a lot about how leaders are challenged by the global environment and need to develop greater strategic agility and make better big decisions. No argument. But a prerequisite to becoming more agile and adaptive in thinking and decisions is to have a strong foundation of intellectual clarity, capability and emotional resilience. With so much cognitive and emotional energy consumed by the stress leaders feel in the current business environment, where do we start to build this foundation? Neil Armstrong taught us that the decisions we may perceive as insignificant are in fact the key.

We as humans share the same internal voices (dimensions) which speak to us and ultimately determine our communication, decisions and actions. When we better align and integrate these dimensions, we effectively reduce the stress or "noise" in our cognitive and emotional systems, and in the process create more internal "free space" to deal with leadership challenges and decisions. We all intuitively recognize these voices, but we may not think often or deeply about which one is driving most of our decisions and behavior, especially at an unconscious level. But Neil Armstrong did.

For our leadership development purposes we categorize these internal voices as:

- Higher Self: the dimension which prompts us to act in concert with universally shared values, primarily: integrity in communication and making decisions based on what we believe will benefit the most people affected over the long term. i

- Primal Self: the dimension which prompts us to do what feels best, in this moment, for me. Under great duress or stress often the urge to flight, fight or freeze, and not necessarily an unhealthy response if led by your Higher Self.

- Rational Self: the dimension which seeks to reduce uncertainty and variation in outcomes. Of course it is impossible to calculate with certainty all the immediate human responses to leadership decisions, and enormously stressful even to try.

- Our Higher Self will not shut up. Although quieter, it continues to prompt us unconsciously to correct the violation of integrity or higher good. Of course rather than choosing this healthy alternative, most of us choose rather to rationalize, blame and ultimately create a scenario where we are the victim rather than the violator…a false narrative that only requires continual justification and unconscious use of our intellectual and emotional energy.

Our brain will not tolerate this dis-ease. The "noise" and stress created from lying to ourselves causes the normal synaptic integration and communication between our limbic system and neocortex to be reduced, so that we become even less balanced and agile in our thinking, decisions and behavior.ii

Our brain will not tolerate this dis-ease. The "noise" and stress created from lying to ourselves causes the normal synaptic integration and communication between our limbic system and neocortex to be reduced, so that we become even less balanced and agile in our thinking, decisions and behavior.ii

Through the exercise of his Higher Self in many "small" decisions, his rational dimension, unburdened from trying to calculate all the external odds and responses, had abundant "free space" to create ideas and a clear path to achieve his higher purpose. Free of the guilt, shame, bitterness and powerlessness that comes with endless cycles of unconscious and futile attempts to rationalize past decisions and behavior, he was unfettered by emotional baggage so that his Higher Self could create the positive emotional fuel to sustain him over a lifetime of leadership and contribution.

Thus he did not need to expend great energy trying to "manage the elephant" of his emotions. They, along with his rational dimension, were naturally aligned with his Higher Self through years of consistent decisions and training. So it was easy for NASA to recognize who would use the prestige and honor of being first to most advance their larger mission and purpose. iii

If you want to make great and agile leaps in leadership effectiveness and decision-making, pay attention to small decisions and communication, for it is those that build the integrated or disintegrating internal system you will live with for the rest of your life. Finally, if you are curious how agile Armstrong was in his thinking and decisions….read what he did when there were only about 20 seconds of fuel remaining during the moon landing. Because he was led by a higher voice, he was free, mindful, present, agile and a decisive leader long before those topics were prominent. It might be worthwhile to follow in his footstep.

Roy Holley

- For more academic research on universal values a good starting point is the work of Shalom H. Schwartz and his Value Inventory, and of course much subsequent work to address limitations and gaps.

- Since neuroscience has become so trendy it is often hard to separate sound research and fact from "pop" neuroscience. A credible starting point would be The McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT and the Martinos Imaging Center in Boston.

- Chris Kraft and three other senior NASA leaders met in March 1969 and decided Armstrong would be the iconic first on the moon due to his humility and character, and the implications for NASA and the world. The egress/hatch consideration later used in a press conference was for PR purposes only.